|

Yarrow, British Columbia

Edited by

Esther Epp Harder, Edwin Lenzmann, and Elmer Wiens

Hop Industry by Esther Harder | Picking Hops by Ed Lenzmann |

Hop Yards by Ken Hiebert

The Hop Industry

|

The Hop Industry

by Esther Epp Harder

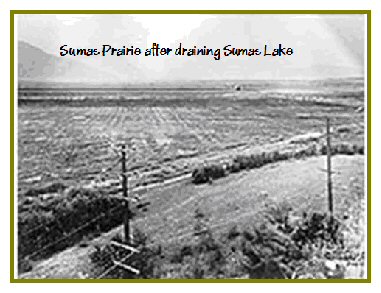

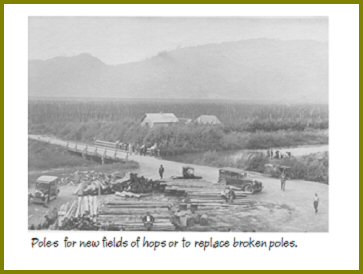

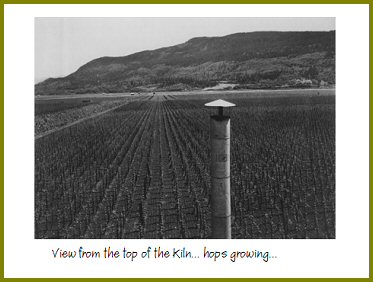

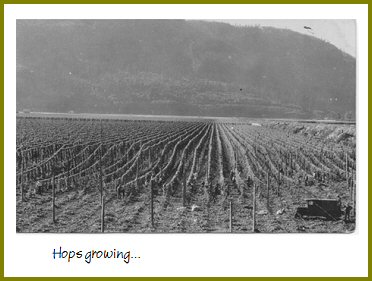

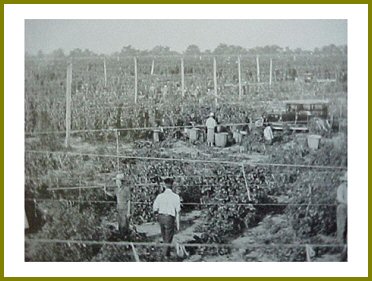

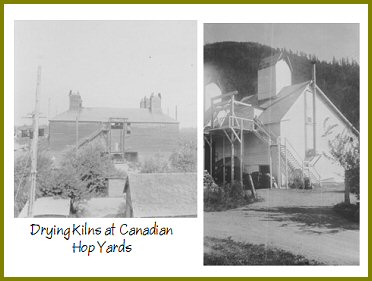

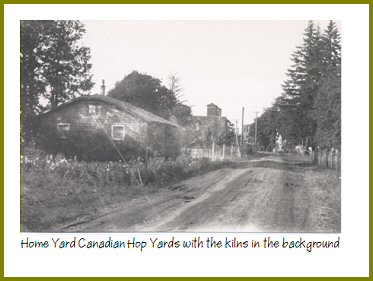

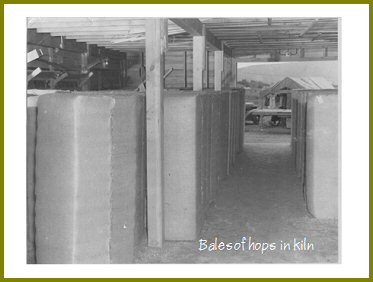

After the completion of the Vedder Canal and the drainage of Sumas Lake, the 30,000 acres of land of Sumas Prairie became available for agriculture. One product that proved successful for many years was hops. Hops grow best between the latitudes of 35 to 55 degrees; require large tracts of land, a plentiful supply of cheap labour, and a large monetary investment in poles, wires, cables, farm machinery and equipment, kilns to dry and compact the hops, and cold storage facilities. Moreover, knowledgeable management and quality hop rootstock suitable to the region are crucial, along with ready access to markets.

|

|

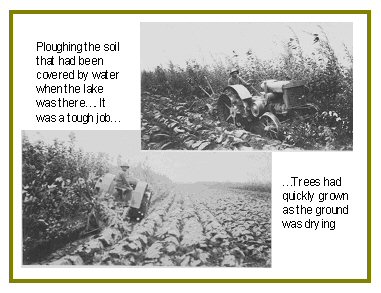

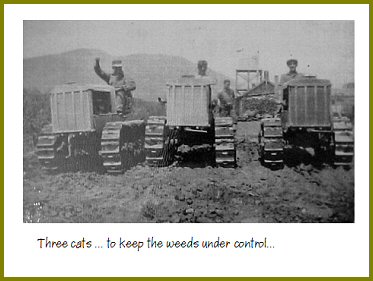

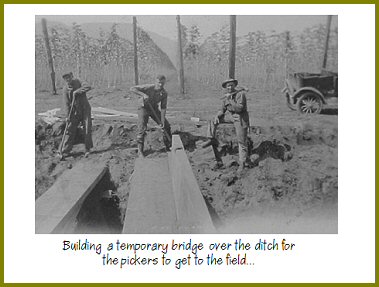

Once Sumas Lake was drained, logs, stumps, and all kinds of debris washed down by the Vedder River were found on the lake bottom above the fertile land of the flood plain. A massive effort was required to make the prairies suitable for the establishment of hop yards. Ditches were dug around the perimeter and through the centre of fields to drain the Sumas flood plain. The water from these interconnected ditches was pumped into the Sumas Canal and the Sumas River, which in turn was pumped into the Vedder Canal near the Fraser River.

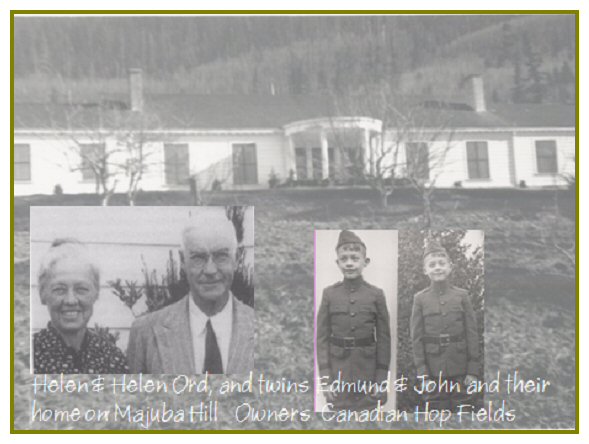

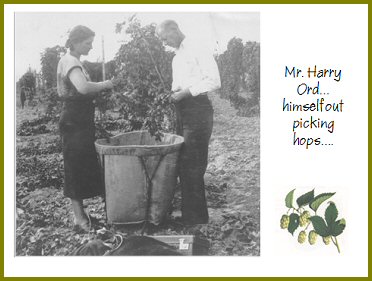

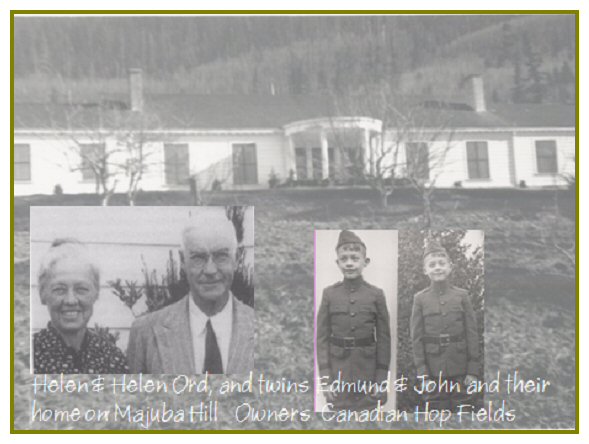

The American Henry Norton Ord, a joint partner of Canadian Hop Yards, and owner of Ord hop fields on Sumas Prairie (Fuggle Hop Garden) and in Kamloops, built a mansion on the western portion of Majuba Hill overlooking Sumas Prairie and western Yarrow.

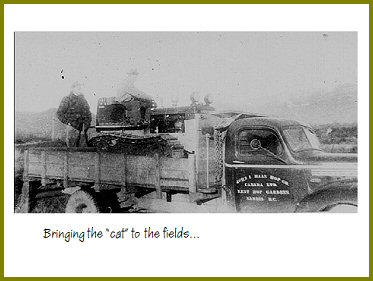

The family of Mrs Ord, Helen Huntington Holladay, had almost a century of experience growing hops. She took over running the company when Henry Ord died in 1955, selling the Sumas fields to John I. Haas, but keeping the Kamloops hop yard (Sleigh 266-67).

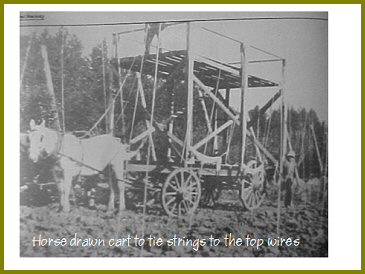

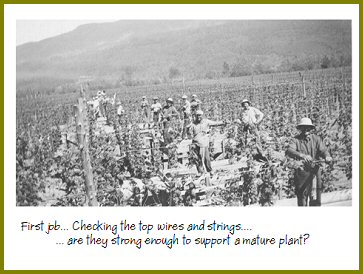

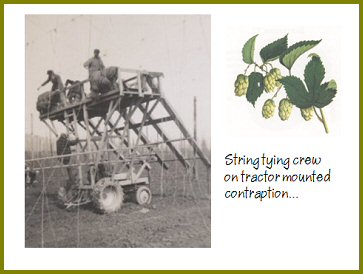

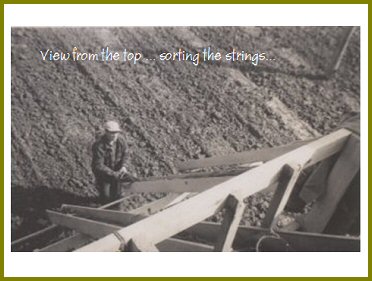

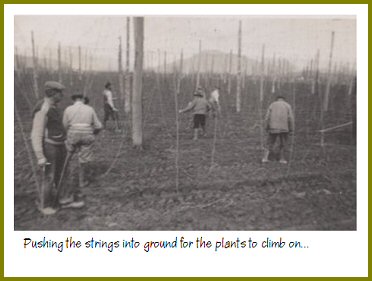

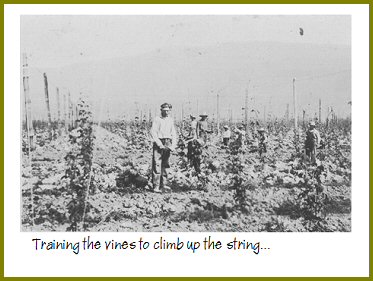

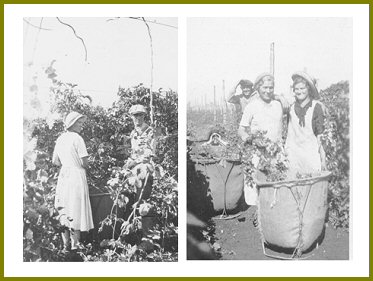

In the middle of spring, workers wind two or more hop shoots clockwise around the twine hanging from the overhead trellis of wires. This process, called training, helps the hop plants along on their way to the top of the trellis. Workers repeat this process until each twine has a suitable growth of healthy hop vines. The timing of this training in relation to the weather will determine the yield of the hop plants at harvest time.

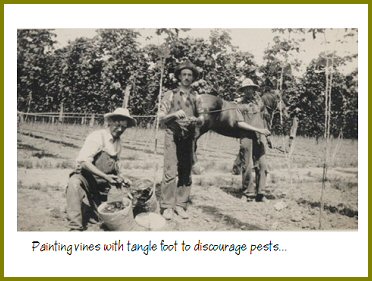

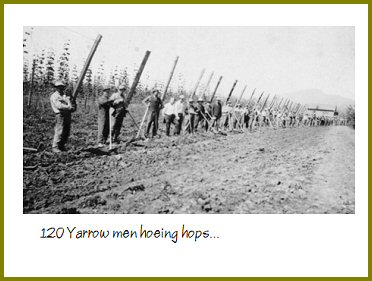

Hop yards are cultivated during the spring and early summer to keep weeds under control. Weeds can intefere with the growth of the hop vines, and provide an environment for insects and hop plant diseases.

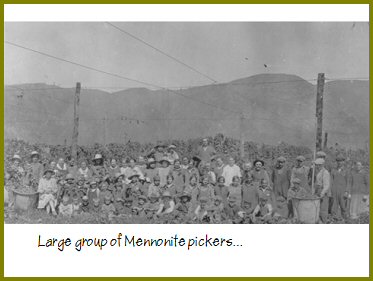

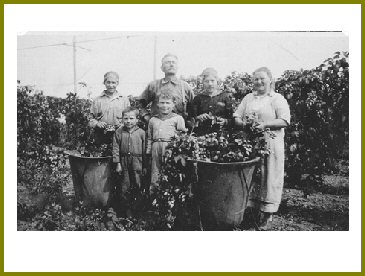

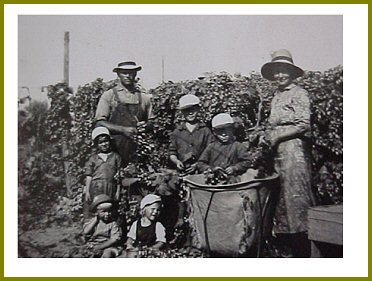

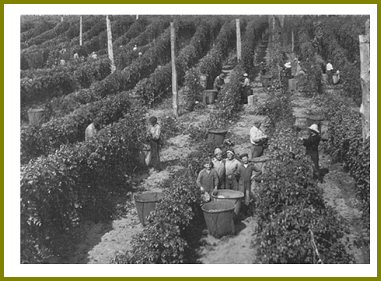

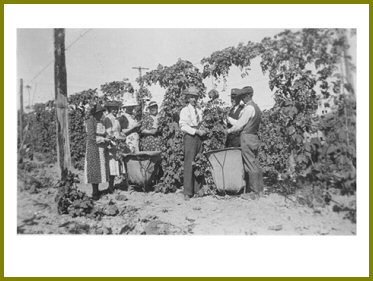

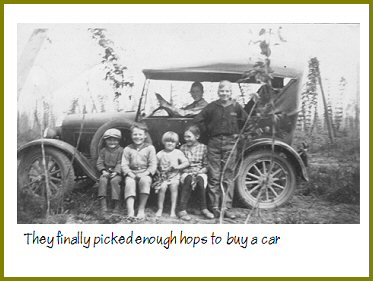

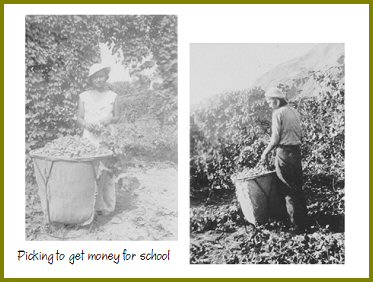

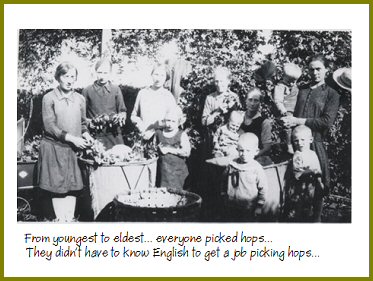

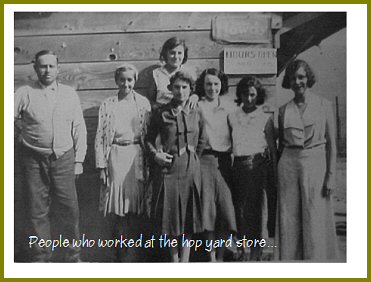

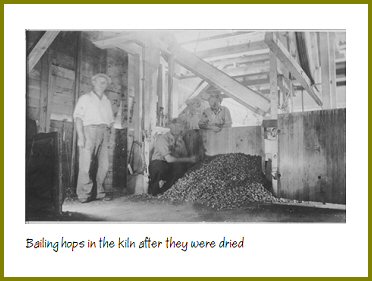

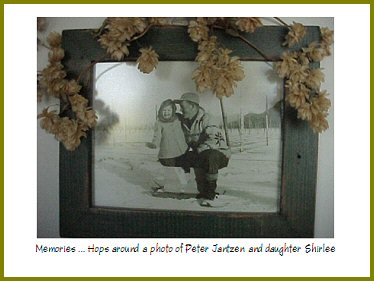

Harvesting hops was very labour intensive. The destitute residents of Yarrow and its environs were proficient workers ready and willing to take on the considerable task of harvesting the fruit of the hop plants. The picking hops was often a family effort, starting in late August and lasting well into the fall.

Some Mennonite men were of the interesting habit of wearing suits when they picked hops.

Looking very natty complete with vest, tie, and hat!

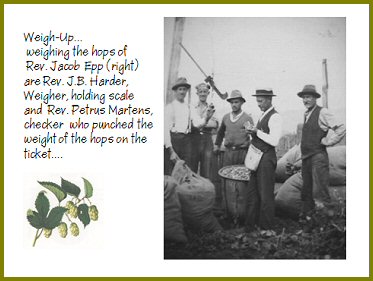

Weigh-up Time!

|

|

Picking Hops

by Ed Lenzmann

I have only the most vague memory of being in the hopyard during the late 1940's with my mother, my sisters, some friends, and on occasion, my father. How we got there I do not know. I do remember a friend telling me there were bears in the mountains north of Greendale. That's all I remember. But my mom remembered how on one occasion a lady headed for the portable biffy from one direction found herself in a race of sorts with Karl Bartsch, coming from the opposite direction. His young compatriots yelling, "Run Karl, run", cheered him on. Every time she related that incident she laughed so hard, the tears ran her cheeks.

Things really began when I started going to the hopyard without my parents. Just my sisters, my friends, other young people, and old ladies. (All ladies were 'old' to someone about eight or nine years old.) It must have been the end of August, because I do not recall missing school to pick hops. We got up terribly early. I thought it was just past the middle of the night. After a quick breakfast we grabbed our lunches and headed for the end of the driveway. Dressed warmly in our absolutely oldest and most tattered clothes we must have looked like a bunch of little beggars.

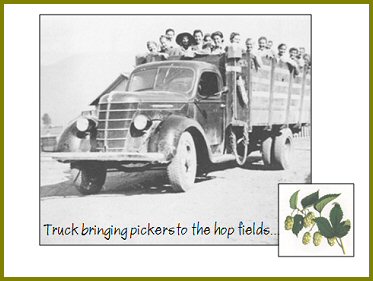

It was cold, dark, and very quiet. With enormous anticipation we listened for the truck (likely Yarrow Freight and Fuel or freaks and fuels, as we called it) coming either up Central or down Stewart. The back of the truck was accessed by a short ladder; it had a covered roof and was equipped with three long benches. Our preference was to get on our knees and lean against the raised tailgate; but as I recall, sometimes that was prohibited. At times when we turned a corner the benches would tip over, and sometimes we helped things along, just to upset the 'old' ladies. When the sky was clear (and I have no recollection of picking in the rain) we were treated to a most stunning sunrise over the rugged mountains to the east when the truck turned left into the Sardis area.

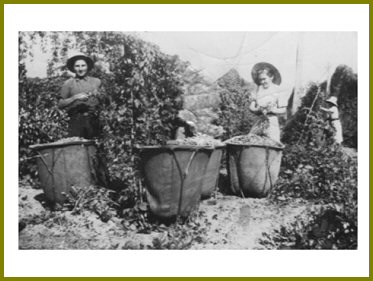

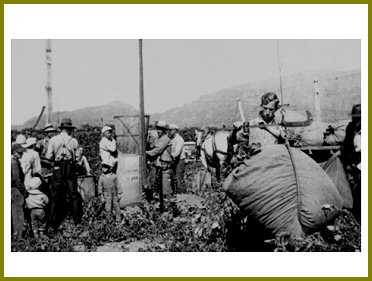

Arriving, we called for 'wire down' and then got to work, or not. We filled the basket more or less, dumped the contents into a sack, and started over. Finishing an area we called for 'wire up' and started over. Stories, gossip, singing, and visits from the less motivated filled the day. Periodically the water truck with tin cups attached by string came by. We were told not to drink that water. Too many germs. We brought our own.

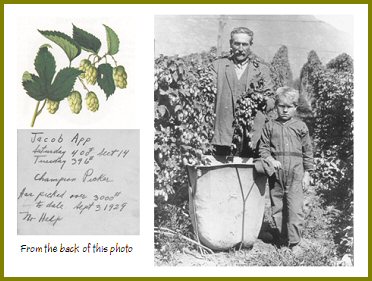

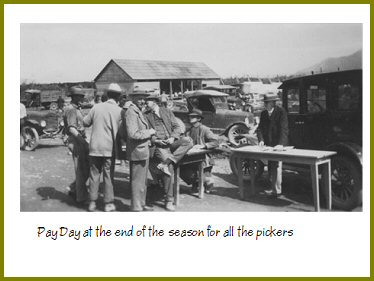

At the end of the day we lined up to have our sacks weighed. Mr. Henry Janzen from Stewart checked them. Those with leaves and/or kluters (clods of dirt) had to stand outside the line and clean them out, often to the taunts of their friends and acquaintances in the line. To our young minds Janzen was the enemy and that didn't help matters when he led the singing in Sunday school.

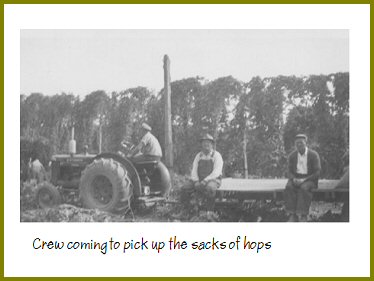

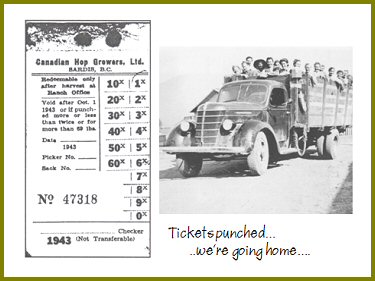

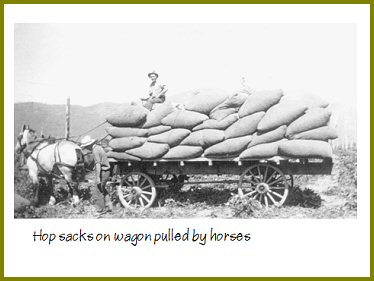

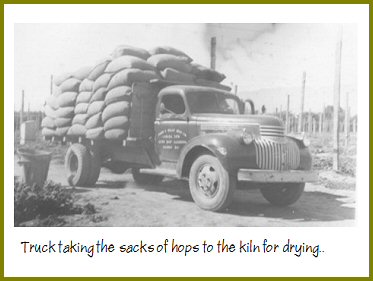

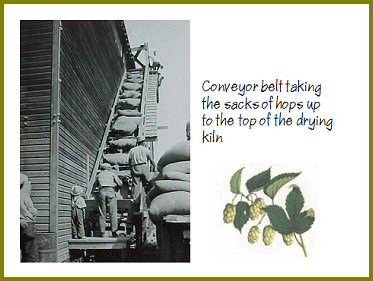

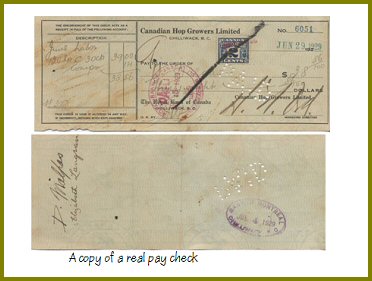

The sacks were weighed with a scale hung from the overhead wires. Who did the weighing? I don't remember. Then they were tossed on to a wagon with balloon ("airplane") tires, pulled by a tractor, or on to a pile, to be picked up later. The weight of each sack was called out to Nick Boschman, standing off to the side and looking very official. He clicked out the amount on the precious little yellow card we brought home to our parents each day. From that card they could tell whether we'd been goofing off. In my case it wasn't necessary; my sisters made sure that I never goofed off.

When we arrived home each day our fingers were black from a somewhat sticky yellow substance in the hops. We used a gritty soap called "Snap" to clean our hands each day.

Being Mennonite Brethren we got saved periodically and in part, our behaviour in the hopyard depended on whether we were saved at that particular time. Our parents were absolutely convinced that the hops we picked were used to make yeast, and not beer. At times they argued that if all the hops we picked went for yeast and all of the hops picked by people not opposed to drinking went for beer, it would work out. Had all of the hops been used to make beer, they would never have picked hops. Nor would they have allowed us to pick.

|

|

Hop Yards

by Ken Hiebert

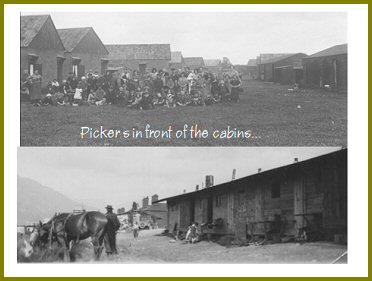

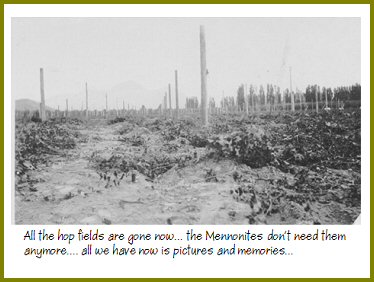

Hop yards were (and probably still are) a common sight around Chilliwack and Yarrow. I remember travelling with my family through Sardis and seeing fires some distance from the road at night. I was told these were the bonfires of Native Indians who were working on the hop harvest. A generation before us the hop harvest involved large numbers of people. People stood in the fields and picked the hops by hand. Around Yarrow were many people who had once picked hops. My parents were among them.

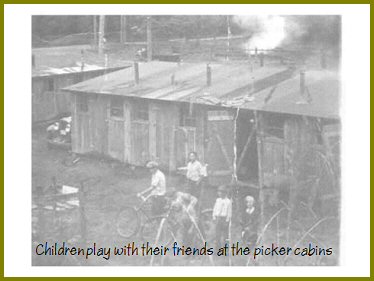

When I worked outside Yarrow on the Sumas Prairie there was still a row of shacks that had once housed hop pickers. I was told that during the harvest a whole town sprang up, with butchers, policemen, prostitutes, etc.

I was told that the hop yard I was in had once been owned by a Mr. Orr. From his home on Vedder Mountain he could watch the work through binoculars and see who came to the end of the row last. He would have this person fired. Anyhow, that was the story.

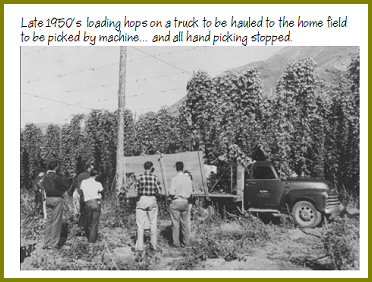

By the time I got involved in the early '60s the vines were cut and brought into a shed where they were picked by machine. But there was still a need for casual workers. This would be local young men like myself and a variety of workers brought in from elsewhere. This included rough characters from the city and one year I remember that some Doukhobors were brought from their encampment near Hope. I was pleased to see that one of them had a large CND peace symbol across the back of his jacket. (I was already drawn to radical politics. Perhaps I had already been to my first year at UBC.)

I have more than one positive memory. I remember coming down from Majuba Hill to Eckert St. before sunrise, going to meet my ride. I remember this because one morning I heard Mrs. Wolfe singing as she moved their herd of cows. Another morning there was a strong wind and the air was very clear. As the sun came up over Vedder Mountain it was a ball of white light, completely colourless.

Once we were working next to a corn field. Amongst us was a man with one hand and a hook on his other arm. I think he was Hungarian. He and others went into the corn field and picked some of the corn. With scrap wood in the hop yard we built a fire and put the corn directly on the fire, still wrapped in leaves. A third of the cob was charred and inedible. But the rest was OK, although I missed having butter, salt and pepper.

So we had a labour pool familiar with work in the hop yards. For a number of years there was a group of young men who travelled from Yarrow to Kamloops to work in the hop harvest there. Among them were Gerald K., Gordie P., Gordie and Walter T.

|

|